CONTACT

DOWNLOADS

- Brochures - download - PREVIEW

- Brochures - download - PREVIEW

- Maps

- High resolution photos

- Calendar of events

There is archaeological evidence in the western section of Coastal Poljica which dates back to the Stone Age.

There is archaeological evidence in the western section of Coastal Poljica which dates back to the Stone Age. Not far from this cave, one hundred meters below and to the west, there is another, smaller cave, locally known as Ponistrice, whose floor is covered with bone breccia, brown clay and numerous stones. A few flint tools have been found in this sediment, indicating presence of man in early Palaeolithic times.

Not far from this cave, one hundred meters below and to the west, there is another, smaller cave, locally known as Ponistrice, whose floor is covered with bone breccia, brown clay and numerous stones. A few flint tools have been found in this sediment, indicating presence of man in early Palaeolithic times. Examples of early Neolithic specimens are seen in the findings of the “Cultural group of Hvar”, which are comparable in every way with those from the caves of Mark and Grapac on the island of Hvar, and with other Neolithic caves in the Šibenik and Poljica areas. In cultural terms they fall within the so-called Adriatic Littoral Group, or the wider grouping of Mediterranean Neolithic. Fortuitous prehistoric findings from the cave on Babnjača belong to the same group. Certainly the oldest traces of human activity found to date are from Turska Peć and Ponistrice.

Examples of early Neolithic specimens are seen in the findings of the “Cultural group of Hvar”, which are comparable in every way with those from the caves of Mark and Grapac on the island of Hvar, and with other Neolithic caves in the Šibenik and Poljica areas. In cultural terms they fall within the so-called Adriatic Littoral Group, or the wider grouping of Mediterranean Neolithic. Fortuitous prehistoric findings from the cave on Babnjača belong to the same group. Certainly the oldest traces of human activity found to date are from Turska Peć and Ponistrice.

There is evidence of continuous settlement in coastal Poljica only from the late Bronze Age and the Iron Age. Organised life is indicated by the presence of mounds and ruins, the latter most frequently on the tops of hills, at strategic points which afforded protection and a broad view over the surrounding area. The remains would have been structures which served as refuges for temporary residence and provided a degree of defence against enemies. Some of these fortresses served as look-out posts overlooking tracks, passes and ravines. Above the Turska Peć there are the remains of the Barić fortress and on Letuša above Zeljovići there is a large semi-circular fortress which, like that on Babin Kuk west of the church St. Maxiumus, could also have been a dwelling place. Further to the east there are the remains of the Jurišić castle above Duće. On the eastern-most peak of Babnjača above Priko there is a wide stone embankment, the remains of a fortress which would have been extremely important strategically, since it overlooks the Brač Channel and the Mosor hinterland and is in a position to supply advance warning of attacks on the important site of Gradac above Zakučac. Some mounds were once graveyards with numerous graves; Others indicate the earlier presence of Illyrian tribes, for example the well-known boundary-marking stone-embankment running from the promontory of Orij to the church of St. Mark in DUće, the “Mucla longa” in the Sumpetar collection of deeds (the “kartular”) or the “Per sassa” in the Austrian register of contributions (the “katastik”) and the mound of Pišćenica which marks the boundary between Pituntin and Narestin.

There is evidence of continuous settlement in coastal Poljica only from the late Bronze Age and the Iron Age. Organised life is indicated by the presence of mounds and ruins, the latter most frequently on the tops of hills, at strategic points which afforded protection and a broad view over the surrounding area. The remains would have been structures which served as refuges for temporary residence and provided a degree of defence against enemies. Some of these fortresses served as look-out posts overlooking tracks, passes and ravines. Above the Turska Peć there are the remains of the Barić fortress and on Letuša above Zeljovići there is a large semi-circular fortress which, like that on Babin Kuk west of the church St. Maxiumus, could also have been a dwelling place. Further to the east there are the remains of the Jurišić castle above Duće. On the eastern-most peak of Babnjača above Priko there is a wide stone embankment, the remains of a fortress which would have been extremely important strategically, since it overlooks the Brač Channel and the Mosor hinterland and is in a position to supply advance warning of attacks on the important site of Gradac above Zakučac. Some mounds were once graveyards with numerous graves; Others indicate the earlier presence of Illyrian tribes, for example the well-known boundary-marking stone-embankment running from the promontory of Orij to the church of St. Mark in DUće, the “Mucla longa” in the Sumpetar collection of deeds (the “kartular”) or the “Per sassa” in the Austrian register of contributions (the “katastik”) and the mound of Pišćenica which marks the boundary between Pituntin and Narestin.

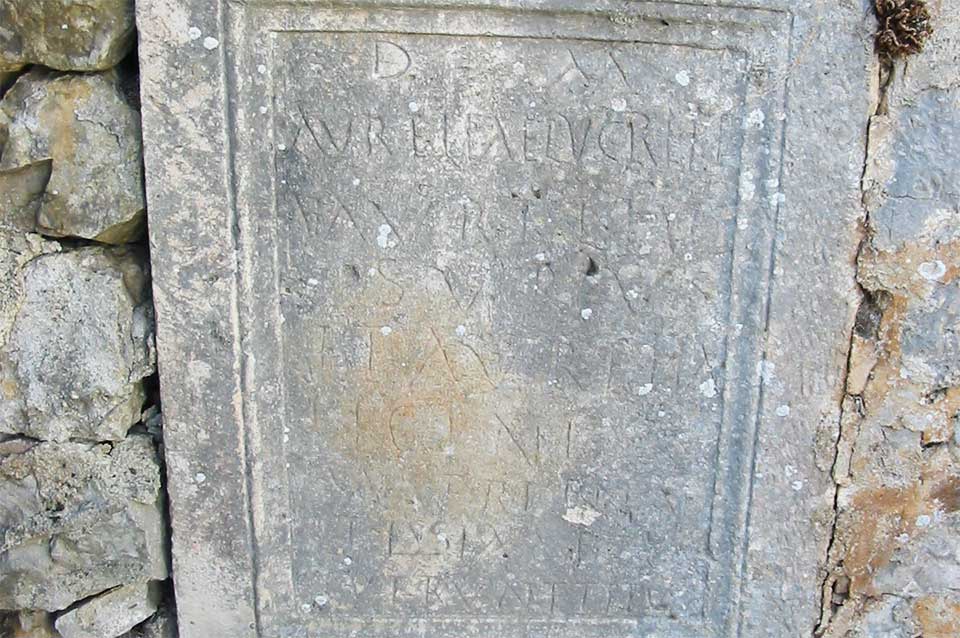

In 1991 archaeologist Romeo Jerčić and the author of this article found a stone inscription bearing the name Nertastina in the wine-cellar of one Mrs. Julija Klarić, widow of the poet Branko Klarić. Until this discovery, the only physical evidence of the existence of the Nerastina tribe, other than in ancient sources, had been two outer boundary stones found long ago.

The stone slab with the inscription measures 43x33x17 cm and has an edge raised by 4 cm and lettering 2.6 cm high. It most probably comes from Sustipan.

The inscription therefore refers to the temple dedicated to Diana and Asclepius which the Nerastina people renovated completely. One further fragment of the inscription, measuring 22x18x11 cm and mentioning the Nerastina, was found in the autumn of 1991 by Romeo Jerčić in a stony border around his land on Sustipan.

These inscription are very similar, having almost the same size of letters and both referring to the renewal of some public building.

In 1914, Don Frane Bulić reported that Filip Kalebić, son of Ivan, found on his land in Sustipan many ancient walls, five plinths, a great deal of building material, sections of a white mosaic etc. On the same land there are still two pieces of an architrave with an inscription and part of a column 50 cm in diameter and 130 cm in length. The architraves had been used subsequently as weights for pressing olives. These two stone beams, measuring 153x66x42 cm, are imposing and most probably were parts of an earlier building. Sculpted in letters 7 cm high we see text:

EX TESTAMENT (O) (P)ATER FECIT.

It is possible that this refers to a temple, perhaps relating to these recent findings. It is also possible that it refers to the ancient memorial grave mentioned by Don Frane Bulić. As we have seen, the one thing we have not found so far is any physical evidence of the cults of the Nerastini; the neighbouring Pituntini worshipped Silvanus, and the Onastini Liber and Augustus. With the references to Diana and Asclepius we have a fuller picture of the cults of the Illyrian tribes living between the Cetina and Žrnovnica rivers.

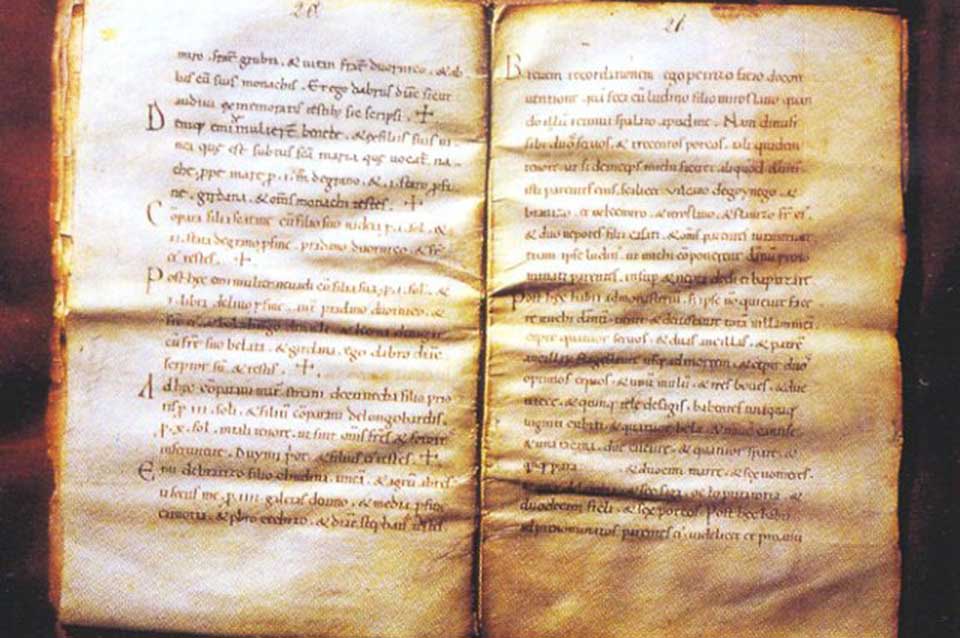

The Sumpetar collection of deeds (the “kartular”) of the Benedictine monastery of St. Peter in Selo (Sumpetar) provides the most comprehensive information about Poljica in the Middle Ager. These invaluable documents, now kept in the archive of the Metropolitan Chapter House in Split, contain valuable data about the life of the nobleman Petar Crni Gumajev of Split, who built a Benedictine monastery on his land in 1080 at his own expense, alongside the earlier church of St. Peter. In his later years, Petar Crni retired into this monastery, founded by him and his wife Ana. He adopted the Benedictine habit and eventually died there. He was buried in an early-Christian sarcophagus bearing an inscription which can now be seen in the Museum of Archaeological Remains in Split. It is presumed that the first four lines of the inscription were written by Petar himself and that it was completed by Dobre after Petar’s death.

The Sumpetar collection of deeds. the “kartular”, is essentially a description of the geographical state of the pious endowment which had its largest estates in the coastal area of Poljica. it is therefore a first-class document showing the toponymy and economic relationships of the area in the Middle Ages. The monastery of St. Peter in the village ceased to exist after the Mongols penetrated into Croatia, and by the 14th century the properties and the deserted monastery devolved to the Archbishop of Split. The ruined church was subsequently repaired and the front side of Petar’s sarcophagus came to serve a new function: it became the altar “menza” in the new church. This is known only from extant archaeological documentation.

On Sustipan there is the double-apsed church of St. Stephen close to St. Peter’s. It has early Romanesque stylistic details and was made within the supposed early Christian complex, the site of which awaits further research. The northern chapel id dedicated to St. Antony the Abbot, and the southern chapel to St. Stephen. The latter is decorated with a marble altar partition without gables or architraves. Different sections are made from different kinds of marble, and it can be accurately dated to the 11th century. Systematic research will be needed to determine whether this altar partition once belonged to the church of St. Stephen’s or to the old church of St. Peter.

Other early Christian remains on the mountain are the chapel of St. Andrew on Oblik, St. Maximus with its Medieval graveyard with stone grave-tops, and the church of Our Lady of the Snow (Stomorica) above Duće, with a very interesting graveyard in which monolithic stone slabs cover natural clefts in the rock.

The church and graveyard of St. Mark in Duće was built exactly on the outer border of the Naarestin and Onastin tribes at the beginning of the Middle Ages..

tia.

It is not known to what extent this region was subject to outside attack during its inhabitation by the Croats.

Previously, during the Byzantine-Gothic wars the mountain refugees were again used by the aboriginal population, who withdrew into the old fortress settlements of coastal Poljica.

The first significant reports of incomers are in documents such as deeds of donation by Croatian national rulers.

The peace treaty of 839 AD between the Croatian Duke Mislav and the Venetian Doge Tradenik mentions St. Martin in Podstrana.

The question of the political affiliation of coastal Poljica at that time has various aspects.

The coastal and western parts of Middle Poljica recognised the authority of a Croatian ruler of the Neretva region or of the Archbishop of Split.

Later feudal attempts to usurp the area hastened the creation of the Poljica Principality which was better able to resist the interests of other rulers (the families of Kačić, Šubić and the Split Chapter House). The coastal area was part of the Poljica principality from the year 1444 until its dissolution during the period of French rule.

From the time of the Greek colonisation of Eastern Adriatic there is evidence of the Nesti and Bilini tribes on the coast between Split and Omiš. For example, Epetion, one of the first Isa (the Island of Vis) trading centres on the mainland, was situated at the mouth of the Žrnovnica river.

Hellenic graves from the same era on the hill of Mutogras contained many ceramic fragments and artefacts, indicating the presence of cultural and trading connections with the Vis and aboriginal Illyrian inhabitants.

When the Illyrians (Delmati) became established in the region betwrrn the Krka and Cetina rivers, they also settled in Poljica. Pliny mentions three Delmati tribes living between the rivers Žrnovnica and Cetina, and the fortresses of Petuntium, Naraste and Oneum.

Several boundary inscriptions which marked the territories inhabited by these tribes have been found. One is close to Krč and the church of St. Luke on Dubrava and dates from first century. It was placed there during a boundary dispute, which was settled for a second time on the order of governor of the Province of Pison during the rule of Emperor Claudius.

The inscription marking the Onastin territories was found near the church of St. John around Greben above the graveyard of Sustipan and dates from the time of Emperor Caligula.

From the time of the Greek colonisation of Eastern Adriatic there is evidence of the Nesti and Bilini tribes on the coast between Split and Omiš. For example, Epetion, one of the first Isa (the Island of Vis) trading centres on the mainland, was situated at the mouth of the Žrnovnica river.

Hellenic graves from the same era on the hill of Mutogras contained many ceramic fragments and artefacts, indicating the presence of cultural and trading connections with the Vis and aboriginal Illyrian inhabitants.

When the Illyrians (Delmati) became established in the region betwrrn the Krka and Cetina rivers, they also settled in Poljica. Pliny mentions three Delmati tribes living between the rivers Žrnovnica and Cetina, and the fortresses of Petuntium, Naraste and Oneum.

Several boundary inscriptions which marked the territories inhabited by these tribes have been found. One is close to Krč and the church of St. Luke on Dubrava and dates from first century. It was placed there during a boundary dispute, which was settled for a second time on the order of governor of the Province of Pison during the rule of Emperor Claudius.

The inscription marking the Onastin territories was found near the church of St. John around Greben above the graveyard of Sustipan and dates from the time of Emperor Caligula.

The Sustipan site has many ancient remains, which have never been systematically investigated. There are many inscriptions of a sepulchral nature (inscriptions on gravestones), coins, late-antique ceramic (terra sigilatta), scattered pieces of mosaic and some remains from buildings (tegule pansiana – tiles) suggesting that it was the site of a villa rustica. The area around Trstenik has an abundance of stone artefacts used for olive processing (“torkulari”, from the Latin “torculum” – to press), parts of olive presses, stones carved to receive oil, etc. Throughout the region from Suhi Potok through Sustipan and Stiničin to Solin there is evidence of the existence of human activity in many of the sheltered bays. Fragments of mosaic found in Dugi Rat near Žilići belonged to Roman villa.

The Sustipan site has many ancient remains, which have never been systematically investigated. There are many inscriptions of a sepulchral nature (inscriptions on gravestones), coins, late-antique ceramic (terra sigilatta), scattered pieces of mosaic and some remains from buildings (tegule pansiana – tiles) suggesting that it was the site of a villa rustica. The area around Trstenik has an abundance of stone artefacts used for olive processing (“torkulari”, from the Latin “torculum” – to press), parts of olive presses, stones carved to receive oil, etc. Throughout the region from Suhi Potok through Sustipan and Stiničin to Solin there is evidence of the existence of human activity in many of the sheltered bays. Fragments of mosaic found in Dugi Rat near Žilići belonged to Roman villa.

The Romans also colonised the area of Krilo Jesenice before the Nerastini and Pituntini who were then able to use the assets which the Romans left behind. Near Gradišće there are remains of a Roman necropolis with graves similar to those in Manastirine from Salona. Older written works mention parts of mosaics, ancient coins, remains of walls and water cisterns lined with impermeable mortar, parts of which are still visible today.

The Romans also colonised the area of Krilo Jesenice before the Nerastini and Pituntini who were then able to use the assets which the Romans left behind. Near Gradišće there are remains of a Roman necropolis with graves similar to those in Manastirine from Salona. Older written works mention parts of mosaics, ancient coins, remains of walls and water cisterns lined with impermeable mortar, parts of which are still visible today. Remains of an early Christian triple-aisled basilica were found in the wide bay of Sumpetar in 1911, at the site where in the 11th century Petar Crni built a Benedictine monastery and the church of St. Peter, which evidently incorporated both former building and took its name. The foundations of this church are not preserved today because a family house has been built on the site. The only evidence we have is from archaeological findings nearby which include fragments of inscriptions from the 6th century. The date is known from evidence on several pieces of sculpted stonework: bases of columns, capitals and parts of early Christian sarcophagi. Near this church there are also remains of another early-Christian cemetery and basilica of St. Stephen, with an imposing length of about 30 m. There are also parts of sarcophagi, acroteria and grave-tops indicating the former use of the site. Excavations around the old graveyard produced many stone and marble fragments of great artistic value, confirming the significance of the religious site and the settlement to which it belonged. The remains of the two apses and Medieval two-aisle chapel of St. Stephen, later renovated, show the continuity of use of the sacral site up to the present day. We can see late antiquity and early-Christian sections built into the early-Romanesque church of St. Peter on Priko. One can assume that there was a large late-antiquity basilica nearby, of which decorative architectural elements were later built into the church of St. Peter: transennas (grid-like stones serving as support), pilasters, imposts, capitals and parts of sarcophagi from the 5th or 6th century. There are also traces of early-Christian sculpture near St. John on Greben.

Remains of an early Christian triple-aisled basilica were found in the wide bay of Sumpetar in 1911, at the site where in the 11th century Petar Crni built a Benedictine monastery and the church of St. Peter, which evidently incorporated both former building and took its name. The foundations of this church are not preserved today because a family house has been built on the site. The only evidence we have is from archaeological findings nearby which include fragments of inscriptions from the 6th century. The date is known from evidence on several pieces of sculpted stonework: bases of columns, capitals and parts of early Christian sarcophagi. Near this church there are also remains of another early-Christian cemetery and basilica of St. Stephen, with an imposing length of about 30 m. There are also parts of sarcophagi, acroteria and grave-tops indicating the former use of the site. Excavations around the old graveyard produced many stone and marble fragments of great artistic value, confirming the significance of the religious site and the settlement to which it belonged. The remains of the two apses and Medieval two-aisle chapel of St. Stephen, later renovated, show the continuity of use of the sacral site up to the present day. We can see late antiquity and early-Christian sections built into the early-Romanesque church of St. Peter on Priko. One can assume that there was a large late-antiquity basilica nearby, of which decorative architectural elements were later built into the church of St. Peter: transennas (grid-like stones serving as support), pilasters, imposts, capitals and parts of sarcophagi from the 5th or 6th century. There are also traces of early-Christian sculpture near St. John on Greben.